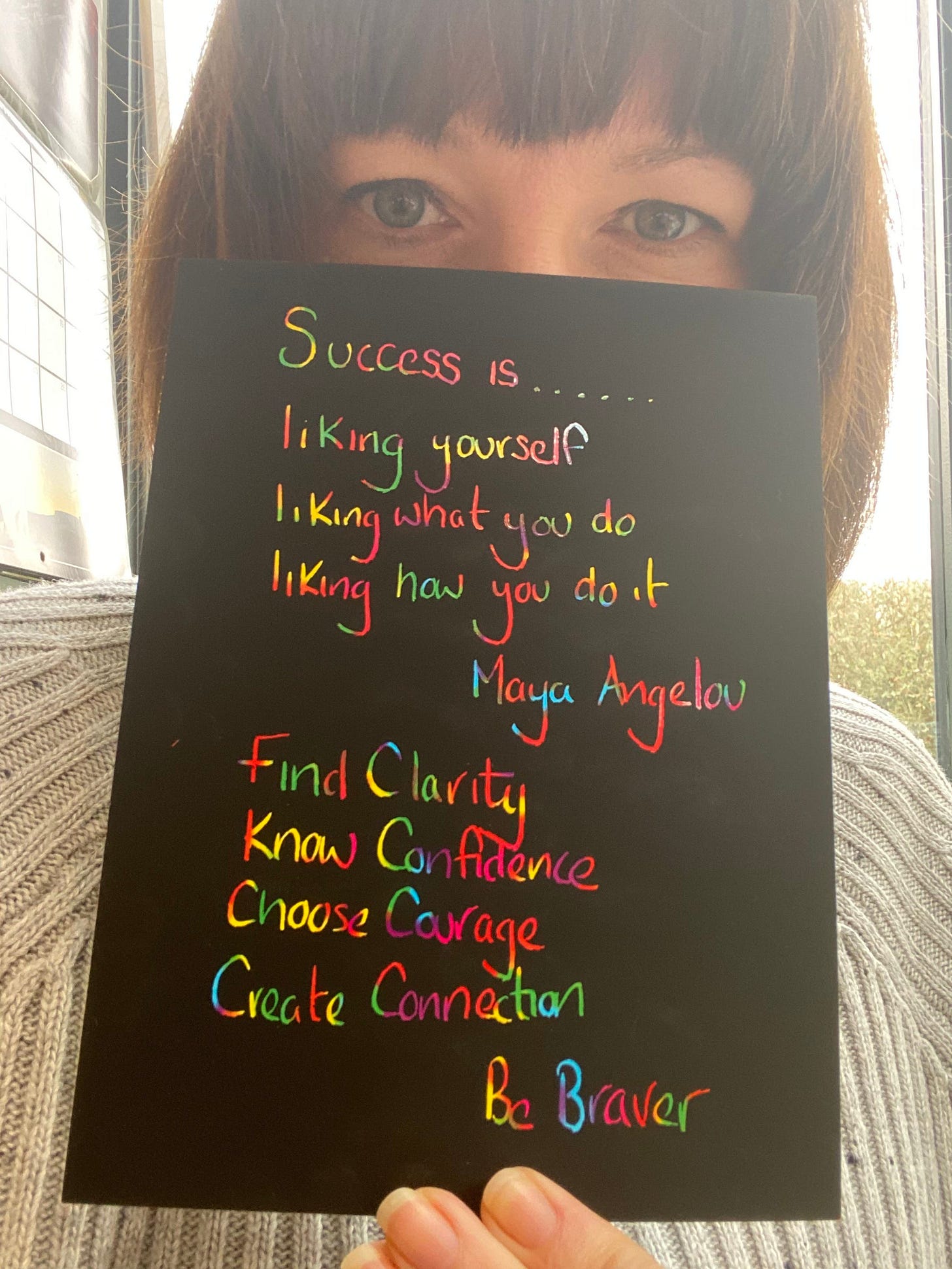

I've learned that 'making a living' is not the same thing as 'making a life'. —Maya Angelou

Transforming our relationship to the idea of 'success'.

What’ve you got for me? He said, bursting through the door while waving silently with his eyes and a twitch of his head at the camera guy. It was a signal for the camera to stay outside the glass fishbowl of a boardroom and film from there. I’m not entirely sure when I’d grown accustomed to the awkwardness of my boss always having people documenting his every move.

This was to be a private-ish meeting, filmed but no audio. Three of us had been working on the penultimate pitch for weeks; me dialing in the strategic thesis, our Chief Creative Officer leading creative systems that would fuel the thesis, and our SVP, Account Lead ensuring this would wow the pants off every client who was seeking to tap the wellspring of the disruptive ‘secret sauce’ that hovered around my boss, not unlike his permanent documentary crew.

A little over a year earlier, I’d joined VaynerMedia as the first Chief Strategy Officer1 for the enigmatic digital-first agency. My interview for the role happened in the rear seat of a black Chevrolet Suburban, me wedged in the middle seat between Gary Vaynerchuk and his camera guy, his audio guy and driver up front. Gary’s assistant had explained that the best way to ‘fit me in’ to his schedule was to interview while Gary was shuttled from one of his early morning speaking gigs at a college in Harlem to the agency’s office in Hudson Yards. I’d brought Gary a green juice. I don’t know what my thought process was, but with such unconventional circumstances for an interview, perhaps I was trying to assimilate to the weirdness of it all.

Since my days as a baby strategist, my sights were set on three little letters: CSO—Chief Strategy Officer. For no reason other than it felt like the top rung of the ladder I’d been climbing. I’d never considered measuring my success any other way. Summit the mountain = success. I’d been promised this title via promotion at my previous agency for over a year, leaving me practically salivating with the anticipation of jumping that final step up the corporate ladder. It was like the adult version of the marshmallow experiment. My impatience was equal in measure to the average New Yorker waiting in any line: ripe.

Who’s leading this thing? Gary asked, snapping my attention back into the room.

Yes, right, I’ll kick us off… I said, swiftly slotting into the well-worn groove of my professional strategist mode and starting the pitch we’d rehearsed. As it came time for a transition to my colleagues so they could bring the pitch home, I slumped back in my chair in a way that silently signaled how bone-crushingly exhausted I felt. An involuntarily, vast and exaggerated inhale followed, which seemed to trigger the aperture of my world-view to blow w i d e o p e n.

Was it a dissociative episode? Perhaps. Was I having an out-of-body experience? Absolutely.

Suddenly the words being spoken in the room were garbled, muffled. I hovered near the ceiling, looking down at my colleagues and myself, sitting opposite Gary in a boardroom overlooking lower Manhattan and the Hudson River. Wow. Just 14 months into ‘my dream job’ as CSO, pitching what was arguably an industry-disrupting, proprietary strategic and creative methodology that would operationalize the agency (Gary’s) philosophy on creative, media and how to win in the digital economy.

This was it: the definitive moment of my career. The summit.

Doesn’t feel like you thought it would, does it?

The voice spoke crisply and calmly, emanating from no particular direction, from within me but also all around me. The question travelled over my skin, like a slow-motion scene of a pin piercing a burgeoning balloon, the latex tearing apart and rippling back on itself. I expelled all the air I’d been absentmindedly holding onto in my burning lungs and tried to catch my breath.

What did I hope this would feel like? To be at the summit of my career?

While the pitch continued before me, I silently retraced the steps of twenty years, hoping for a trailer that gives away the plot of the entire film. Let me catch a glimpse of what I’d hoped to feel once I’d ‘made it’ and was finally living my dream?!

N o t h i n g.

Worst trailer ever. No flutter of feelings, just the plot summary and the heroine’s determination to valiantly strive to the top of the mountain. Try as I might, I couldn’t summon any clarity over the sound of the voice now urging “No more. Not this. No more. Not this.”. One week later, I walked into Gary’s office and told him I was leaving—my role, New York City, the burnout, and the deflated career dream that now lay in my hands like a burst balloon.

Tall Poppies and Humble Brags

If you’ve spent any extended length of time in Australia, you’ll have heard talk of ‘tall poppy syndrome’. No, it’s not a medical condition. This deceptively bright, cutesy term is used to describe when people are resented, disliked, criticized, discredited, or cut down in other ways because of their achievements and/or success. ‘Cutting down the tall poppy’ is a culturally ingrained, social phenomenon in Australia (and New Zealand, I’m told) that subversively shows up in micro relationships (friendships, workplaces and neighbourhoods) through to the macro public stage (mass media).

There is no such thing as a ‘humble brag’ Down Under. Bragging of any kind is a shortcut to a tear down. The bigger the brag, the harsher the tear down. Even big dreamers who haven’t yet achieved their success are not safe from a pre-emptive strike. As a kid growing up in Australia in the '80s, it’s wasn’t uncommon to be told by an adult to “wake up to yourself!” (translation: quit dreaming) or “pull your head in!” (translation: stop boasting). In fact, adults often throw quips like this at each other, under the guise of a friendly joke. It can feel like everyone’s inner critic got together and formed one giant, amorphous outer critic.

I lived in Sydney or Melbourne for almost two thirds of my adult life. That said, I left to pursue my dream in New York City almost a decade ago, so I can’t say if tall poppy syndrome is still a cultural norm now. Perhaps my Aussie friends can leave a comment with their more recent experiences.

In my personal reality, my father’s perspectives on achievement (especially at school and work) along with his subconscious need to out-run his family history of living on the poverty line meant that striving for success was deemed a virtue in my childhood.

Achievement = Approval = Success.

Needless to say, any tall poppy rebuffs from my peers could never overshadow the deep longing I had for my father’s approval. Subsequently, I became Type OA; Over-Achiever.

Moving to the United States in 2014, I was struck by how fervently US culture celebrates ‘success’. To an outsider, it seemed being talented, at the top of your game, and/or materially successful in America effectively grants you an immediate ‘celebrity’ status. A stark contrast from what I witnessed growing up, seeing many Australian talent, artists and creatives move abroad to ‘make it’ elsewhere. Was it just because other markets held greater possibilities, or was it something else taking us abroad? I convinced myself that my own move to the USA was for the promise of greater possibilities (subtext: greater achievements ahead), but in truth I was running away from my leading role in Season 1 of Break Up With Burnout. (Spoiler: it takes three seasons for me to finally learn the real reason I burn myself out).

While I was happy to leave my Chief Strategy Officer dream in the gutters of Manhattan, I wasn’t quite ready to leave the USA. I needed a new visa. A friend introduced me to my immigration attorney, who began assessing my eligibility for the coveted O-1 Visa. This particular avenue of US work visa required me to demonstrate extraordinary ability in the sciences, arts, education, business, or athletics through sustained national or international acclaim. My attorney told me I had a strong chance. As he asked me to send him every piece of public recognition I’d ever received as evidence for my petition, he added “Now, don’t be ‘Australian’ about this. This isn’t a time to be modest about your successes.” Clearly he’s worked with enough Aussies to clock our pattern of hiding or downplaying any achievements to avoid resentment from others.

As requested, I assembled an enormous file of the press clippings, awards, speaking gigs, interviews and creative accolades I’d gathered over the journey of my career… all the while thinking this feels like a charade. But, the charade worked. All of these ‘achievements’ somehow meant I was worthy of acceptance and a new US work visa. Success, right?

I started to question the Success Math we were taught. Who does Achievement = Approval = Success cater to, anyway? The individual, or the machine?2

Our nation's success is tethered to Gross Domestic Product (GDP), a metric solely focused on economic health. But what about the broader indicators of our society's wellbeing – its people's health, safety, and happiness? GDP alone fails to capture the true pulse of a nation, leaving us blind to the fundamental aspects of humanity. We've lost sight of the basics of humanity in pursuit of an elusive American Dream, leaving a trail of broken spirits in our wake.

—Katherine Libonate in Elmo Reveal's We’re Not Okay

Flipping through this ‘portfolio of my career’ now, I feel hollowed out. In those pages, I see the long hours, the endless striving, the days I collapsed from exhaustion, the sacrifices my kid made as his mother tried to take on the corporate world and solo-parent at the same time. Waves of my annual existential crises about working in marketing (arguably a ‘Bullshit Job’3 that only exists to inflate GDP) violently flood my senses all at once. Memories of all the times I’d attempted to pivot into something more meaningful. Ahhh yes, this is why “I wish I hadn’t worked so hard” is in the top five regrets of the dying.4

“I work and come home.”

Just like having all your savings in a single stock, it’s a bit risky. You’re overexposed to the risks of work: a bad day at work is now a bad day of life; your sense of meaning and purpose is also dependent on work; and you don’t even want to think about what a lay-off might mean.

—Bree Groff on What Work Should Be

I refuse to let that be one of my regrets when my day comes. It’s time to divest of achievement culture and live a #PortfolioLife5—diversify my investments for a joyful, connected, deeply nourishing human existence.

The Original Essence of ‘Success’

It’s because I’ve experienced both ends of the spectrum, living in the contrasts of a world where achievements can be ridiculed and they can be celebritized, my inner word-nerd wants to explore and debate our definitions of success and the unintended consequences of allowing our social conditioning to define it for us.

A fellow Aussie (who is no stranger to the perils of tall poppy syndrome), activist and writer

shared a note about ’s piece The Myth of the ‘Successful Writer’. Elif’s succinct summary of the etymology of ‘success’ grabbed me and won’t let go.“It is an old word, success, that takes us back to the 16th Century. At the heart of it lies the Latin root of succedere, which means “come close after”. The word successus signifies “a happy consequence or a good result or an outcome that makes one feel content”. It is as simple as that! Nothing more.”

—Elif Shafak of Unmapped Storylands

Oh what it is to feel this definition land so viscerally as an ache in my bones while also feeling so overcome with the grief that we (speaking mostly to Western society here) are taught quite the opposite. In the words of

, “we’re trained from birth to willingly take part in an addictive system which will eventually destroy us”.6If we want to change the world, we need to be unrealistic, unreasonable and impossible.

—Rutger Bregman, Utopia for Realists

I get it, changing the outcomes of late-stage capitalism and consumerism feels unrealistic most days. How do we evolve from here? What is the solution? These big questions are paralyzing. That’s when I remind myself of the words of John Maynard Keynes: “The difficulty lies not so much in developing new ideas as in escaping from old ones.”

I choose to believe the escape starts with small steps beyond the edges of what’s acceptable, normalized or even comfortable.

Keynes quote reminds us that “we must recognize that humans are susceptible to the allure of familiar ideas, systems, and ways of thinking. Whether due to comfort, habit, or fear of the unknown, we often cling to established notions even when they no longer serve us.”7 It begs us to search for the cracks in our socialized beliefs and stretch our fingers through to graze against the unfamiliar, just for the creative curiosity and wonder of it all.

I close my eyes and am transported to springtime living on Kralingse Plaslaan in Rotterdam, Netherlands in early 2021. My son and I are spending eight months flirting with the idea of moving to Europe, spending 1-2 months ‘living like a local’ in various communities and experiencing the slower pace of a European lifestyle. In Rotterdam, I reclaimed my mornings, creating a container for the sacred rituals that fill me with feelings of contentment. Starting every day this way utterly transforms my creativity, connection to my intuition, and the measure of contentment in my days. Sacred mornings is a practice that I’ve returned to recently, after Season 3 of career burnout. Each morning, spinning new dreams of a life fully lived and beginning each new day with a cup full of contentment that makes those dreams feel real right now. These are my baby steps, what are yours?

What fills your cup with contentment?

Imagine a time when you felt the most deeply nourished by life? Describe what was present and true at that time.

How can you bring more of this into your days, starting now?

Write a new definition of success, one of your own design, one that aligns to your big dreams (and resists society’s expectations).

Share your big dream and new definition of success in the comments.

Yep, it’s true. I worked with the King of hustle culture, Gary Vee.

I recently finished reading Utopia For Realists by Rutger Bregman, a Dutch historian. It’s dry but a thought-provoking read. If dry, Dutch historians aren’t your thing,

more evocatively summarizes Bregman’s thesis about the insanity of GDP being a measure of national success in her piece, Elmo Reveals We’re Not Okay.From what I can tell, the term ‘Bullshit Jobs’ was originally coined in 2013 in this Strike Mag article by anthropologist David Graeber and then immortalized in his book Bullshit Jobs: A Theory in 2018. Graeber explores the existence of meaningless jobs and analyzes their societal harm. He contends that over half of societal work is pointless and becomes psychologically destructive when paired with a work ethic that associates work with self-worth.

“Top five regrets of the dying” is a summary from the book of the same name by palliative nurse, Bronnie Ware.

The idea of #PortfolioLife is credited to

. Bree still stands as one of my most favourite people to have had the pleasure of collaborating during my years in New York City. Follow her.Read the full piece here: “crave less, live more: the pursuit of contentment in our runaway capitalistic world”

Reference: socratic-method.com

Also - and you may have written this elsewhere - what is something you learnt from your time with Gary that you still find useful? x

Thank you so much for the mention in your beautiful piece. I am thrilled to finally learn the real definition of success "a happy consequence or a good result or an outcome that makes one feel content”. My definition of success too has evolved greatly over the last few years.